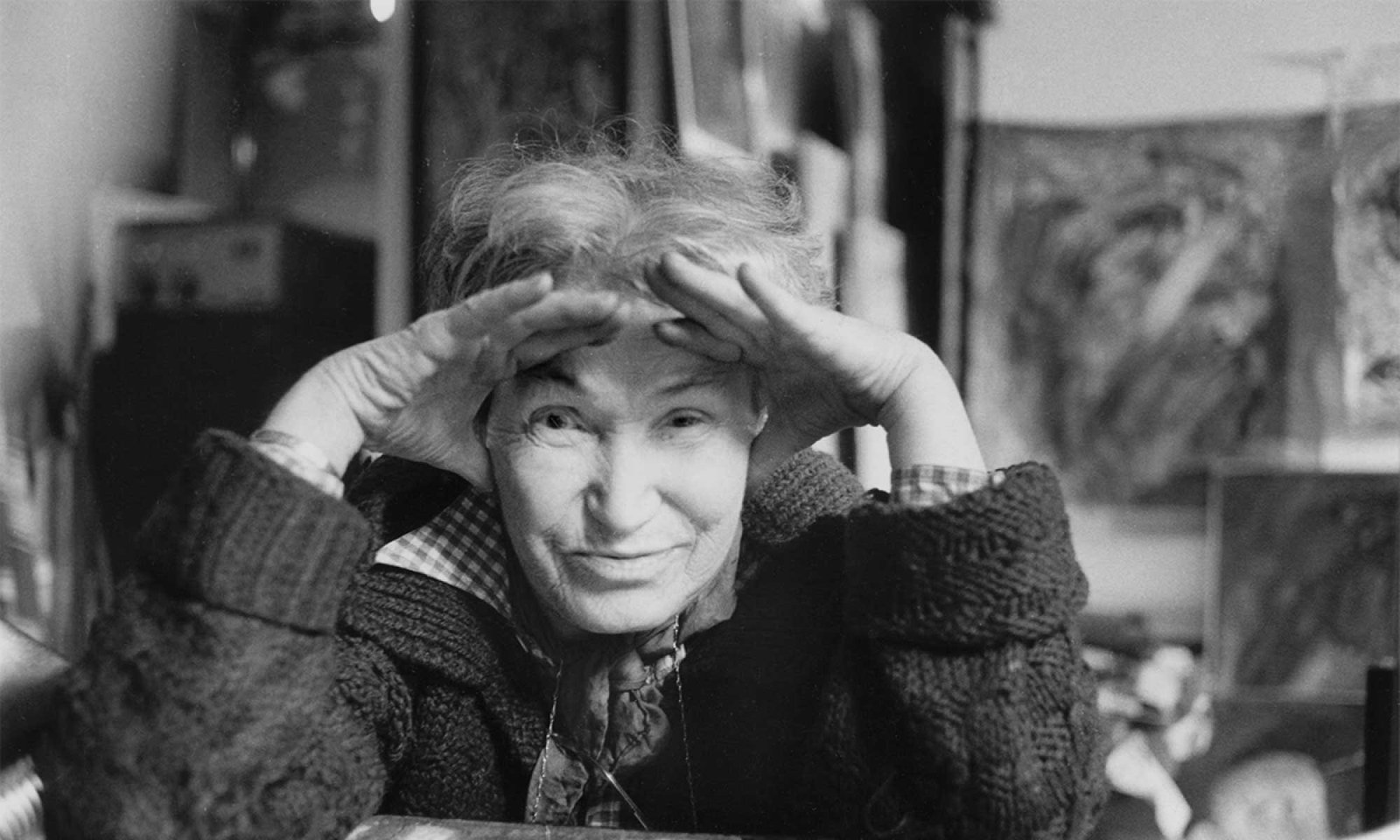

Karskaya is first and foremost a “character,” as one Parisian art critic wrote in the first biography to be devoted to the artist. The critic went on to describe her as: “A sort of dandy who could sport a romantic cape and lace jabot with as great an ease as the unique outfits she designed for herself. A woman both formidable and feared, with a biting wit, a caustic sense of humor, and at times a sharp tongue, who was loath to abide by the numerous concessions that her career’s success demanded. Neither a socialite nor an outcast, she managed to conquer the freedom she needed to create paintings, collages, tapestries, objects, sculptures, and the tall mannequins her granddaughter would later call “Billis-billis.”

Ida Grigorevna Shraybman was born on July 5th, 1905, in Bender, Bessarabia (ex-Russian territory, part of present-day Moldova/Transnistria) to a Jewish family of rich farmers. Karskaya, who was to become a famous French artist of the Second School of Paris and an important figure of the 1950’s informal art movement, was born the second of five children in a bustling home, with close and distant cousins remaining as recurring characters throughout her life. Her father was a landowner fascinated by technical progress, a passion which prompted him to invest in agricultural machinery… and to declare bankruptcy on several occasions.

At the age of 17, having completed the Gymnasium, Ida decided to leave Rumania to study abroad (she had become, by the end of World War I, a Rumanian citizen). Drawn to France, she knew that mentioning her project to her parents would only lead to its immediate rejection. So she talked about studying medicine in Ghent, Belgium, but still had to scheme around: courted by a young man at the passports’ office, she managed by a change of her date of birth to make herself three years older and avoid her parents’ veto.

She remained 18 months in Ghent’s Medical Faculty before obtaining her transfer to Paris.

In an interview with Vladimir Tchinaev, many years later, she was to describe how bored she felt in medical school: “… during classes, I would get bored and doodle around on a piece of paper – an old habit of drawing.”

Immersed in the Russian artists’ Bohemian lifestyle, Ida was bound to find in Paris her true home, all the more so, as she wrote, as “the Russian artists’ Bohemian lifestyle constitutes in Paris a genuine stratum of culture. Despite our poverty and hardships, we had read a lot, we had attended every conference by Shestov and Berdyaev; we had seen and learned a great deal.” She goes on to say: “My husband Serge Karsky and I attended the ‘Green Lamp’ receptions organized by Merezhkovsky and Guippius.”

Her activity as a painter remained concealed for many years (she signed her first paintings with her maiden name), the time for her to assert herself and gain self-confidence in the face of her friends and colleagues, as well as in the world of art galleries and critics.

After the war, there was almost nothing left of Soutine’s influence in Karskaya’s art, except for a comparable skill and pictorial genius. Like many other painters, she had been deeply changed and affected by the war and the difficulties that ensued. Immigrant artists had parted ways, some of them pursuing an avant-garde art with a desire to move forward, while others sought to return to their pre-war roots. Karskaya’s first exhibit in Paris in 1946 – with a preface by Francis Carco – in a major left bank gallery leaned towards the latter inclination, in a quest to find heirs to the legacy of such important pre-war painters as Utrillo, Soutine, and Valladon, and to come back to “tasteful pre-war paintings.” Such an aesthetic approach was quick to collide with Karskaya’s need for independence and novelty, a search for a new path that would lead her to abstract art, and ultimately, to the dismissal of sectarianisms of all kinds.

After her husband’s death in 1950, Karskaya began to work relentlessly, creating series of artworks whose titles either correspondent to events in her own life (“España”, “Mexico”), or to events that, despite being imaginary, had a crucial significance for her (“Lettres sans réponse,” [Unanswered Letters] “Gris quotidiens” [Daily Grays]). Though several milestone series that contributed to her fame may be stated, we must remember a permanent feature of her work, whatever the format, medium (canvas, paper, fabric, tapestry, collage), or time of creation (from 1945 to 1990, the year of Karskaya’s death): that of a full-blown pictorial mastery and a constant pursuit of the avant-garde.

The series “Jeux Nécessaires et Gestes Inutiles” [Necessary Games and Useless Gestures] (1949) was followed by the series “España” after a trip to Spain in 1953 – a country still under the yoke of Franco, but whose customs, people, and painters Karskaya admired greatly.

“Gris Quotidiens” [Daily Grays] (1959)

“This gray of time and life, this gray Karskaya hammers away at as if to wrest its secret from it, haunted by the notion of an invisible space that must be conquered at all costs.” This gray she described as daily matches her state of mind at the time as well as the aesthetical criteria that were to remain hers until the end, in opposition with the fiery, even violent, and colorful American aesthetical standards of the time (with the notable exception of Tobey).

Gris Quotidiens, 1959, 51×71 cm.

After her trip to Mexico, Karskaya went on living for nearly 30 years, working ceaselessly, without any interruption. During this last period, she became deeply interested – though not exclusively – in contemporary tapestry, working on a tapestry created by herself in her own studio, in keeping with a method, an aesthetic and a technique that brought her fame within the world of weavers.

Karskaya never stopped changing artistic themes and mediums, “covering a wide artistic range, from the cerebral to the sensitive, from abstraction to expressionism, from informal to impressionist art, from comedy to pathos.” Karskaya always assured: “I know what I defend: I defend freedom in Art… Art, above all, means absolute freedom.”

And she adds: “The most important thing is to have doubts.”